Apple Paves the Way For Apple

THERE’S a certain meme among tech commentators concerning innovation vs. commoditization, and it goes like this:

Innovators are companies that think up radically new ideas for products that nobody is currently selling. They do the R&D required to make those products a market-viable reality; then (for a time) they reap the rewards of their efforts, selling mostly to people who want the latest, cutting-edge technology, and are willing to pay a premium to get it.

Commoditizers are companies that spend little on R&D — instead, they copy already-proven products. They figure out how to manufacture those products more cheaply, more efficiently, and sell them to a larger audience of more budget-conscious buyers.

An innovator like Apple can be successful for a while with a revolutionary, new product. But in doing so, it “paves the way” for other companies: Soon, the commoditizers (Dell, Samsung) commoditize the market away, leaving the innovator with a relatively small share. The only way the innovator can be highly profitable in the long term is to keep coming out with yet more, revolutionary, new products.

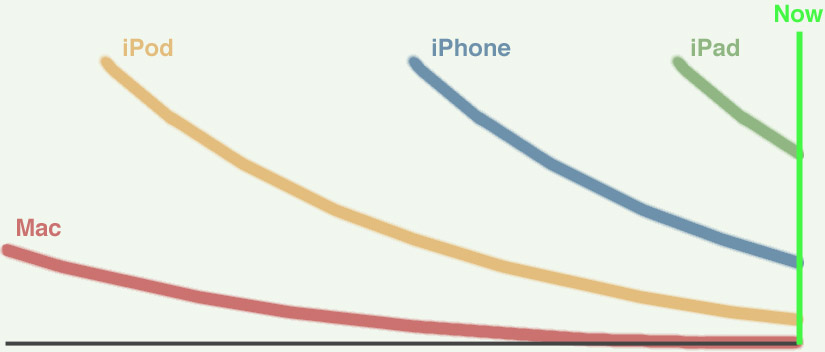

Graphed per Apple, it might look something like this:

Innovator gets commoditized

Now, of course, I just made up this graph. Any self-respecting, Apple naysayers probably would decline to endorse my graph just as a matter of principle. But you can see a strong implication of this graph, or something very much like it, in their analyses. The common thread about Apple’s current situation (compare to the “Now” line in the graph) is that:

- iPad is still doing very well, but slipping, and headed for eventual niche status;

- iPhone is being swamped out of the market by Android, and is just-about already at niche status;

- iPod has been dying for a long time — still here, but nothing like it used to be; and

- the Mac has been in deep-niche position for just about forever.

Apple’s recent good fortune, in this view, is attributable to the relatively rapid release of three revolutionary products (compared to the near-eighteen-year gap between the Mac and iPod). But to stay profitable, Apple must continue to release new, successful, revolutionary products. Apple wouldn’t just benefit from such additional revolutions — the company actually needs them. New revolutions are all that keep Apple from sinking back into a 1987-to-2000-like quagmire. And now that Jobs is gone, how likely are they to be able to keep up the revolutions? Maybe they were really lucky to have them even when Jobs was here. (No wonder Apple’s stock has gone so far down lately.)

How awful for Apple. Better cut your losses and sell your Apple stock now.

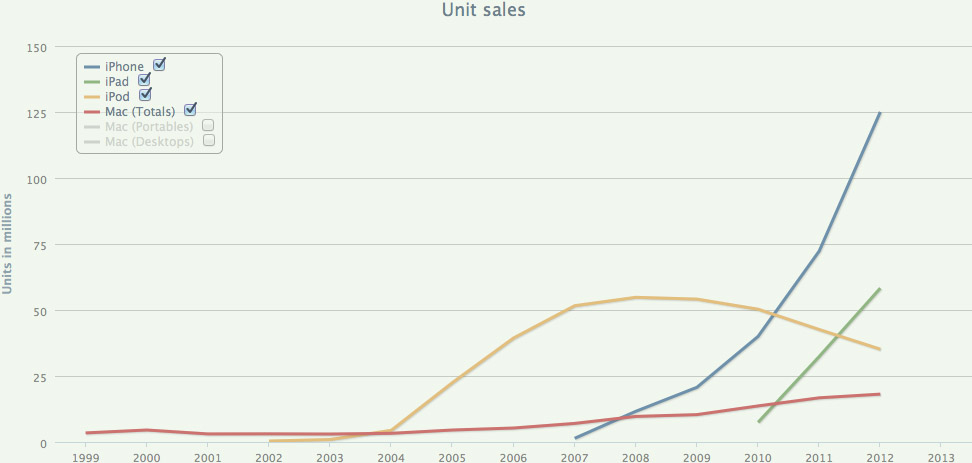

But all you have to do to see that something must be awfully wrong with this view is to take a look at Apple’s unit sales figures for the past twelve years (from Bare Figures):

As I noted before in Apple’s Graphic Failure, the most interesting features of this graph are:

- Except for iPod (which has become less necessary as many people put their music on their iPhone), everything in the graph is going up, and doing so at a constant or accelerating rate.

- Except for iPod’s abrupt take-off in 2005, there is no sudden change in the direction of any of these products’ annual sales. Everything is a long, graceful curve or a straight line.

Does the unit-sales graph look anything like the innovator-gets-commoditized graph? No, it doesn’t. It’s painfully obvious from the unit-sales graph that Apple doesn’t need to make any more revolutionary products at all. It would be great if they did, but they don’t need to. Heck, from what you can tell in the unit-sales graph, Apple might just take over the entire world of computing the way they’re going now, without a single new product.

Both, Not Either-Or

Obviously, something is seriously missing from the innovator vs. commoditizer meme. What it is?

Simple. Apple innovates and commoditizes.

Commodity doesn’t automatically mean the cheapest, bare-bones product. It’s the main market item, the staple item, the one with the largest base of intercompatible users and developers. Throughout the 1990s when Windows PCs ruled computing, a lot of those PCs were not cheap junk, bargain-basement machines. They were pretty expensive. And some of them (high-end “serious gamer” machines) were very expensive. But almost everyone was using Windows PCs, so they were all sold in high quantity, they all benefited from economy of scale, and from a common base of users and developers — they were highly commoditized.

iPad was a revolutionary innovation in tablets when it first came out — and it’s now the commodity tablet! iPhone was a revolutionary innovation in phones, and it’s the commodity phone. iOS was a revolutionary innovation in software platforms, and it’s the commodity platform.

Many tech pundits can’t see this, because — through some combination of misinterpreting what happened in the late 1980s, and just plain disliking what’s happening now — they mutually reinforce among each other a vision in which Apple can’t both innovate and commoditize.

Meanwhile, Apple is doing both. Apple is paving the way — for Apple.

Update 2013.05.23 — Here’s Peter Cohan in Forbes just a month ago:

[T]he construction of a $5 billion palatial headquarters when the company is — at best — between hit products does reflect a certain corporate arrogance.

And just yesterday, here’s Michael McQueen, as quoted by Steve Colquhoun in The Sydney Morning Herald:

The next 12 months will be absolutely critical for [Apple], whether they can release another game-changing product like they did with the iPhone and the iPad. It’s been a long time between drinks for them.

Cohan’s “between hit products” and McQueen’s “between drinks” slyly imply that Apple’s previous hits are in the past — dead or dying — and so the company critically needs new ones.

Update 2013.08.16 — Horace Dediu describes this mentality towards Apple well:

At this point of time, as at all other points of time in the past, no activity by Apple has been seen as sufficient for its survival. Apple has always been priced as a company that is in a perpetual state of free-fall. It’s a consequence of being dependent on breakthrough products for its survival. No matter how many breakthroughs it makes, the assumption is (and has always been) that there will never be another. When Apple was the Apple II company, its end was imminent because the Apple II had an easily foreseen demise. When Apple was a Mac company its end was imminent because the Mac was predictably going to decline. Repeat for iPod, iPhone and iPad. It’s a wonder that the company is worth anything at all.

But is even Dediu buying into it a little himself? The mistake isn’t just thinking that Apple won’t have any more breakthroughs — it’s thinking that the company depends on them. The Mac, iPhone, and iPad have been going up for years. So — although I’d love great new breakthroughs from Apple as much as anyone — where’s the need? Is Apple really “dependent on breakthrough products for its survival?”

Update 2014.04.03 — Harvard professor Gautam Mukunda:

Apple can be an excellent ordinary company or a genuinely extraordinary one. But it can’t be both.

Innovator or commoditizer. Not both. Because I said so.

Update 2014.07.14 — I had hoped I was wrong, but it appears that Dediu really does think this way. Here he is on The Critical Path #118 “The Cook Doctrine”:

What Apple never had, is this type of product which allowed them to sit comfortably and say, yeah, the customer is just going to keep coming back. Yes, they had a niche customer base that would buy Apple consistently, but that was too small to be considered on the same magnitude as these guys [Microsoft and Oracle]. We’re not going to see a billion users, or even a hundred million users as loyal, you know, core, that can be milked indefinitely.

And in that sense, Apple is vulnerable, and Apple is considered, therefore, always on the cusp of failure. Every time the product that it happened to be writing at that moment in time could just fall out of favor; be crushed by competitors who are commoditizing the sector.

And so that’s why Apple today has a lower P/E ratio than the S&P 500. It’s actually considered more vulnerable than the average company. That’s how I would interpret that. They’re not going to be around all that long; that’s what’s implicit in the P/E, is that the profits are going to last X years after today, given what we had last year. That’s the whole value of the company.

Because they’ve never really, not just nailed being a monopoly, but also never sought to be a monopoly, that means that they have to stay on their toes. ... It’s a series of blockbusters, or flashes-in-the-pan if you will. Flashes-in-the-pan are fine if there’s one after the other. And that’s the problem with thinking about it, is that firstly, no one does more than one flash. If they do, you want it to be something that becomes a monopoly. And so they just work on the principle of making sure they have a system in place, even though I think technically it’s not a formula, technically it’s not actually executed like they’re turning the crank, but it so happens that magic is repeatable. That’s the difference.

Dediu’s apparent faith that Apple can keep producing new flash successes is admirable, but what I can’t figure out is how he’s so sure they’re necessary, how he somehow manages to omit the obviously comfortable position of the iOS App Store which, besides being a big success in its own right, also strongly reinforces the ongoing success of iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch, and which may soon be extended to other Apple platforms. It’s like Windows’s 1990s dominance all over again, only this time by Apple — and this time much more closely controlled.

How could Dediu, a noted celebrator of Apple’s success, miss this? The only explanation I can bring myself to believe (and the one that’s seeming more and more likely for Clay Christensen’s and James Allworth’s attitudes also) is simply that after Apple’s ’84-’97 failures, many otherwise highly intelligent people can’t quite bring themselves to believe that the company can ever really be on top. Randomly, even highly successful for brief “flashes?” Sure. But securely on top? Impossible.

Update 2014.07.27 — Allworth’s recent comments on the Apple-IBM enterprise mobility partnership are revealing, to say the least (Exponent podcast #10):

“What’s interesting for me is, if this partnership is successful, which one of the two partners ends up having the upper hand. And I can’t help shake the feeling that IBM is the one that’s possibly getting— I mean, they’re both getting more out of it now, but in the future, who ends up in a better position? I can’t help but shake the feeling it’s IBM rather than Apple.”

“What’s actually in this for IBM? It’s not that hard for them to go out and buy these devices off the shelf right now. You don’t need a strategic partner. If all you’re getting out of Apple are the devices and the operating system, well, everybody gets that.”

“In the short run, there’s nothing [for Apple] to lose. I don’t think they’re giving up anything; they’re not losing anything, and they’re getting a whole bunch of device sales that they otherwise wouldn’t have gotten. In the short run it makes a whole bunch of sense. It’s just, it does feel like — and this is somewhat unusual — it just doesn’t feel like there’s a future where Apple’s in the driving seat in that relationship. It feels like it’s very much IBM.

So here’s the question: Are [IBM] gonna attract a whole bunch of enterprise sales on the back of this, that they otherwise wouldn’t get? Mm. Maybe, maybe not. But they do have the ability to bless an Apple competitor in the future, by saying: You know what? We know how to do all this stuff, we’ve got all this software that sits on top of any platform, any device.

Let’s say Microsoft does split into a vertical and a horizontal company, and they go knocking back to their old foes IBM and say, what will it take for you to put this stuff on us exclusively instead of Apple, on iOS? And IBM’s suddenly sitting in a very nice position to be able to say, well, we’re gonna be kingmakers in the enterprise space, in terms of which device becomes successful or not.”

If you thirst for a real-world example of what might happen when an Apple partner decides to turn on Apple, look no further than Google’s attempt to force Apple to share user data through the iOS Maps app (if Apple wanted vector-based maps and other advanced mapping features that Google was withholding from iOS). Google presumably believed it had the upper hand, since it controlled the back-end mapping system, and Apple only had front-end devices. Surely Apple would cave.

Apple didn’t cave. Instead, they built their own back-end maps system (with, of course, all the features Google was withholding), and subsequently dumped Google as a provider of iOS maps. Despite a rocky launch, Apple’s maps system is now working well, and Google has lost all the money Apple was paying for those services.

With regard to the Apple-IBM pact: I see no reason to think they will be at each other’s throats in the future. Allworth, it seems, is confounded by Apple’s success to the point that, in the guise of educated analysis, he shamelessly spins arbitrary fantasies that Apple will get shafted, then will be replaced by — who else? — Microsoft.

Update 2014.11.03 — Karl Denninger doing his best to perpetuate this mantra on RT’s Boom Bust:

Erin Ade: Do you expect Apple to have any future financial results, in terms of products that they put out? Do you say no?

KD: I say no, and my suspicion is that the iPhone 6 is probably the first of the down side within their product line, in that regard. ... when that upgrade cycle runs its course, where’s the next trick come from? ... will enough people buy [iPhone 6] to become relevant in the global commerce scheme, in order to make Apple Pay a viable thing? Um, from a single-source company? I don’t think it happens. ... I think you need to have something in the pipeline. And there may be something in the pipeline we don’t know about. You need something in the pipeline that’s yet another runaway home run. Whether you like Steve Jobs, that was his charm, that is what he was able to do. But you have to remember, he really only hit the ball out of the park once. And that is unfortunately the way these kinds of things tend to work. So what you have to do is have a lot of very high-risk, concept kind of projects running within the company. They all take up a lot of R&D spending. And 90% of them never see the light of day. And you hope you hit the one that the public just grabs onto and has to have. But that’s the difficulty of any company that finds itself in the position that Apple has, in that you have to come up with that next follow-on product. And I don’t see one that’s in the pipeline that’s going to be that.

Update 2014.11.08 — Ben Thompson has started pushing back a bit against the modularity meme; witness Exponent #24:

BT: I also get the argument that you — kind-of part two of the standard explanation for Apple, and I think that our mutual friend Horace Dediu has articulated this quite a bit — is the idea that Apple avoids disruption because its integrated nature allows it to create new products. And to me this is — and correct me if I’m wrong — this is almost an image of a dog or something, like, running ahead of the fire. It keeps escaping disruption by creating new things. And the fear, or the danger, and arguably the discount that Apple had for a long time on Wall Street, was the fear that they wouldn’t be able to keep doing that, especially as Jobs went away. What happens when they stop creating new products? I’m actually not making that argument. ... my argument is about existing products. It’s not that the iPhone is going to get disrupted so they need to create something new. It’s that the iPhone, as-is, is much stronger and has a much bigger moat than, I think, most people articulate.

...

JA: Delivering a delightful user experience is actually, I mean it’s part of the reason why I love their products. But this idea that the user experience alone defends against disruption? I’m not sure— I’m not saying it’s wrong, and you make a really good case for it, but I actually wonder whether there’s not an alternative explanation, in that because Apple is integrated, they’re able to bite off and tackle new jobs that no other company is able to do, and as they evolve the focus on the new jobs-to-be-done, it kind-of staves off disruption because they leave the old job behind, that if they’d just remained focused on, they might’ve had problems with. ...

BT: Honestly, I’m a little confused. I feel like you’re kind-of twisting yourself in a pretzel here to not attribute to the user experience.

Allworth is twisting himself into a pretzel trying to force the integrator-gets-slammed-by-modularity model onto reality. It’s not a good fit.

Update 2015.01.11 — Jonathan Ive in a Vanity Fair interview last October, when asked by an audience member if he felt flattered and complimented by Apple’s designs being closely copied:

Honestly, there’s a danger that I’ll sound a bit harsh. And perhaps a little bit bitter. ’Cause, I actually don’t see it as flattery. ... I actually see it as theft. Because when you’re doing something for the first time, for example with the [iPhone], and you don’t know it’s gonna work ... and you spend seven or eight years working on something — and then it’s copied. I have to be honest: The first thing I think isn’t, oh, that was flattering. All those weekends I could have had at home with my lovely family, but didn’t — but the flattery make[s] up for it? And I think it’s really straightforward: It really is theft. And it’s lazy. And I don’t think it’s OK at all.

Ben Thompson and James Allworth on Exponent #30:

BT: People wanna go on-and-on about Samsung ripping off Apple, and blah-blah-blah-blah, and, like, can you help me understand how Apple has been injured? Like, Apple is the most valuable company in the world. They’ve made an absolutely unprecedented amount of money since the invention of the iPhone. Like, why are— it’s weird; I think it gets into some of this, like, making it part of their identity? Like, people feel, like, personally violated by this? But, I mean, last time I checked, the economic system is doing a very good job of rewarding Apple for innovation.

JA: I remember the Apple-Samsung case, and correct me if I’m wrong, but there was talk of— I think it was with the tablets. One of the Apple execs was, like, oh, I picked up one of those smaller Samsung tablets, and actually, the size is really good; we should make one of these. It’s like, copying each other doesn’t blunt innovation, it spurs innovation. From a consumer perspective, it actually results in better outcomes. And the idea— so the test is, do you really think Apple’s gonna pack its bags and go home, stop creating stuff, if the patent system disappeared? And I couldn’t imagine that happening for a second.

Do Christensen et al. really believe that Apple is at all likely to be run out of its markets by modular commoditizers? Or is that what they want to see happen? Because nullifying all of Apple’s IP would go a very long way to ensuring their prediction comes true.

Update 2015.03.11 — Dediu’s at it again (The Critical Path #144):

Yet another brilliant point [John Gruber] made: he said the P/E ra— and I’ve said, I hate to say this as kind-of I-told-you-so, but I’ve maintained that the P/E ratio of Apple was irrationally low ... And he said that the reason is that Apple is seen as a hit-driven company. I said as much by saying, look, they’ve had five hits in a row, and no one believes that they can have six. And that is why it gets discounted.”

Is the P/E low because investors doubt Apple can have more hits? Or is it because they don’t think Apple will continue to reap stupendous profits from its existing hits? I really wish Dediu would draw attention to this distinction, but alas — he seems happy to ignore it.

Update 2015.04.25 — Allworth, near the end of Exponent #42, jabs Apple with a last-minute barb:

If Apple had 90% market share, I don’t know that we would tolerate a lot of its behaviors.

What behaviors are those? And why should we tolerate them now? Or is Allworth just smearing Apple’s reputation, sowing seeds of guilty-until-proven-innocent, for the future?

Update 2015.05.29 — Clem Chambers in Forbes, back in 2012 with a quite similar position:

“Five Signs That Apple Is A Bubble”

“The craze of the moment is great for a stock price, but it is fragile. The next novelty is hard to find.”

Chambers directly implies that Apple’s hit products are fragile crazes. Is there any evidence that such a thing is actually true? Is there not a wealth of evidence that it’s completely false? Apple has had some products that tanked immediately (e.g. Ping), and others that are in a long, slow decline (iPod, and perhaps iPad). But which Apple products were fragile crazes?

Update 2015.08.02 — Eight months after I wrote this article, Jay Yarow crafted the following gem for Business Insider. He dances around the subject in a state of plausible deniability, but the message still comes through pretty clearly:

“The Story Of The Creation Of The iPhone Explains Why Apple Can’t Just ‘Innovate’ A New Product Every Other Year”

“Microsoft, for instance, is often blasted for lacking innovation despite the fact that it has labs filled with amazing inventions and home-built first-of-its-kind technology.”

“[E]very major technology company is innovative. Without innovation these companies die.”

“The iPhone has less than 20% of the smartphone market. The Mac has less than 10% of the PC market. The iPad is at 32% of the tablet market, and falling. The iPod is dominant, but largely irrelevant today. Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Facebook all own their markets. Therefore, while these companies do innovate, their innovation is not seen as a feast or famine proposition in the same way as it is at Apple.”

“The iPhone was a success, and it was such a success that people just assume Apple can whip up new creations at the drop of a hat. This story shows that making a new product category from scratch isn’t something that happens easily, quickly, or without considerable risk to the whole company.”

Last winter, iPhone provided two-thirds of the profits of the most profitable quarter enjoyed by any company in the history of companies. But just over a year earlier, Yarow wanted us to believe that iPhone “was a success,” and that for Apple, the quest for innovative, new-product categories is “a feast or famine proposition.” Today, with iPhone pulling in about 9/10 of all smartphone industry profits, there is no sign that Apple’s most recent new product category (Apple Watch) needs to sell even a single unit to prevent the famine of which Yarow warns. In fact, the only two Apple products that aren’t doing better than ever are iPod — the only one Yarow called “dominant” — and Apple Watch, which is the new product category on which Apple allegedly depends.

Update 2016.04.04 — Jason Perlow in ZDNet:

“What Apple has is its brand — and customer loyalty to that brand. It sustains them, but it only lasts one innovation cycle at a time. An extinction event always comes at the end of that innovation cycle and they have to rebuild and re-grow the user base again.”

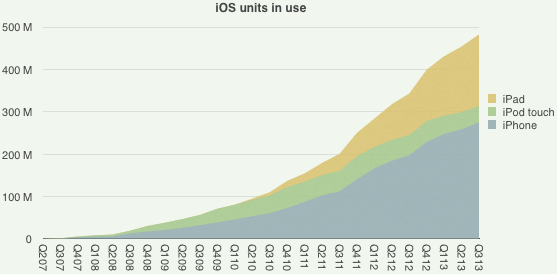

Here’s a graph of iOS devices in use, from Horace Dediu’s Asymco (ranges from ’07 to ’13):

Where are the extinction events, Jason? I’m not seeing them. Either Dediu’s making up a completely fictional history of Apple’s products — or you are.

Update 2016.06.03 — Even though Apple is still exceeding the combined profits of Google, FaceBook, and Amazon, its first year-over-year quarterly profit drop in over a dozen years seems to be emboldening a new set of reasons to think the company’s best days are behind it (Exponent #81):

BT: I am not counting out Echo, because Amazon is an ecosystem company ... It’s all about standardized interfaces; it’s all about not having the best integrated experience, because the best integrated experience doesn’t scale. It doesn’t scale to multiple devices, to multiple services.

...

BT: [T]his whole Apple’s-doomed [view] ... finally is a relatively valid one, because once you get to an area where physical interactions are not the key way to [use a] device, that’s gonna be a problem for Apple.

...

JA: Between [FaceBook and Amazon] ... consuming news, consuming media, and engaging with friends: FaceBook’s got it covered. And it’s increasingly the case that Amazon’s got a lotta the rest of the stuff covered. When you start to position it like that, it’s kind-of crazy the extent to which the two of them are so well positioned for the future.

BT: Right, and it’s to both of their benefit, and this goes back to the article you wrote a few weeks ago, it’s to both of their benefit, and it was critical to their success, that they both failed at phones.

JA: Yes.

BT: Because that enabled them to approach this new opportunity in a horizontal way, as opposed to, if you own the phone, you’re forced into a vertical mindset. ... it’s to their benefit that they’re not tied down to any phone, they’re not tied down to any specific platform. They can sit on top as this meta-platform. Which again, is exactly what Google did to Windows. They sat on top of it, and in a place that Microsoft couldn’t really touch them, just as Apple can’t really touch FaceBook, and can’t really touch Amazon.

JA: You just keep building up the stack. And then, as you start to be the one that’s building at the very top level, it seems to matter less-and-less what sits underneath.

...

BT: Microsoft actually made more money in the decade when they were doomed, than they did ever before previously. Right? In the decade where Google was sitting on top of them, aggregating all the internet content, making Windows irrelevant ... And it’s the same thing right now: iOS, Apple could make as much money as they want, but this building— I’ve been saying this for a few years now, about FaceBook building on top. When FaceBook had their phone thing, I was saying this at the time; this is such a bad idea. FaceBook: You wanna build on top, as an advertising platform, you don’t wanna be a phone, ’cause then you have apps competing with your advertising, and it doesn’t work. And you could see this back in 2013 when I started Stratechery, when Apple was at the peak of their game. But the relevance of owning the OS layer was already fading. And we’re just seeing that, we’re seeing it come out to fruition now. And I feel OK saying this, ’cause, I mean, I wrote it at the time.

JA: It’s fascinating how the financials are such a trailing indicator.

BT: Always.

JA: Yeah, it is. But the extent to which we judge company health so often by financials, and the lag associated, particularly in the building of these— building layer upon layer, it’s actually the case that when these companies look like they’re on top of the world, that actually is, it’s— that’s when they’re in trouble.

Translation: Apple’s game peaked a year before it made the highest profits of any company in history, then did the same a year later. And if it continues to earn similar profits in the coming years, it’s still going down — in fact, that’s a sign it’s going down! And the perpetually wrong, fifteen-year-old, “Apple will get commoditized” thesis sure does sound new, fresh, and once-again-plausible when you phrase it as, “cloud AI will make the device irrelevant/disappear.”

Update 2016.10.30 — Three years ago in The Motley Fool, Jeremy Bowman warned:

“We need to see something new out of the Cupertino kids soon, or like Kodak before it, Apple may be nothing more than a beautiful memory.”

The only really new thing Apple’s released since then is Apple Watch, which — while handily dominant in the smartwatch category — represents only a tiny fraction of Apple’s profits. Two-thirds of Apple’s profits come from the near-decade-old iPhone, and in the past three years Apple has become the most profitable company in the history of companies. The “Cupertino kids” don’t “need” to come out with “something new” to avoid the fate of Kodak. Apple is farther from the position of Kodak than any other company on Earth.

Bowman was utterly, completely wrong. He’s living in a delusional fantasyland where Apple generates briefly successful, fad products. In the real world, Apple has never made such products; everything it produces is either an immediate failure or a long-running success.

See also:

The Old-Fashioned Way

&

Apple Paves the Way For Apple

&

iPhone 2013 Score Card

&

Disremembering Microsoft

&

What Was Christensen Thinking?

&

Four Analysts

&

Remember the iPod Killers?

&

The Innovator’s Victory

&

Answering the Toughest Question About Disruption Theory

&

Predictive Value

&

It’s Not A Criticism, It’s A Fact

&

Vivek Wadhwa, Scamster Bitcoin Doomsayer

&

Judos vs. Pin Place

&

To the Bitter End

design by

design by