Apple’s Graphic Failure

2013.01.20 prev next

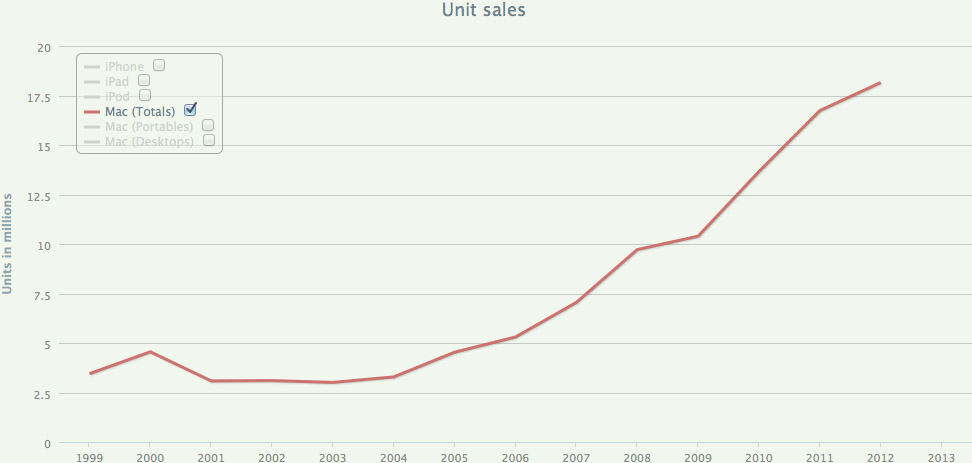

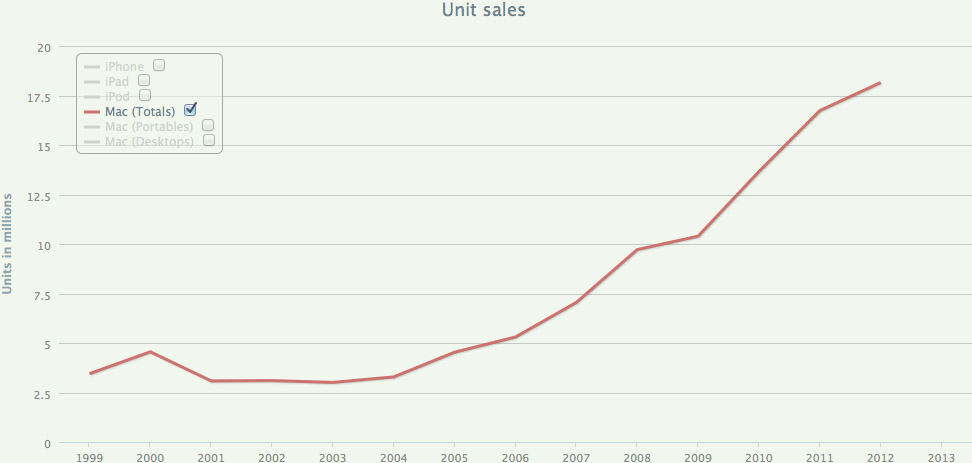

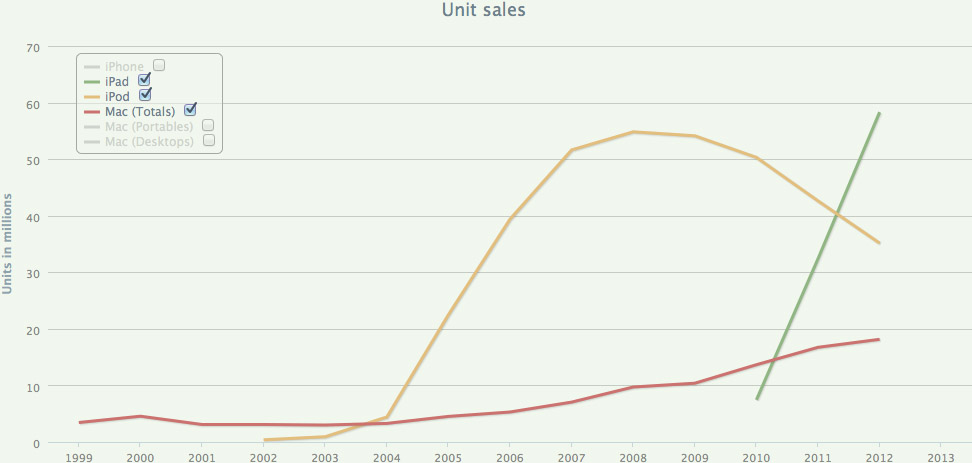

FROM Bare Figures, here’s Mac unit sales over the past dozen years:

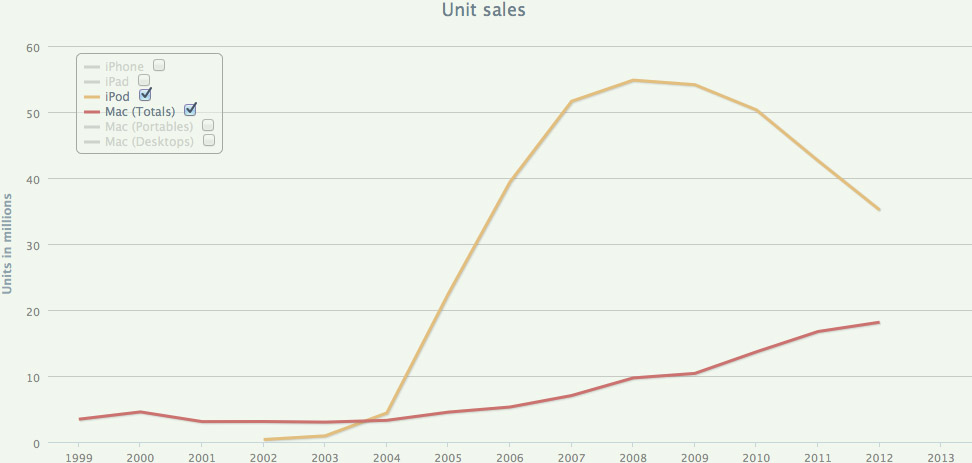

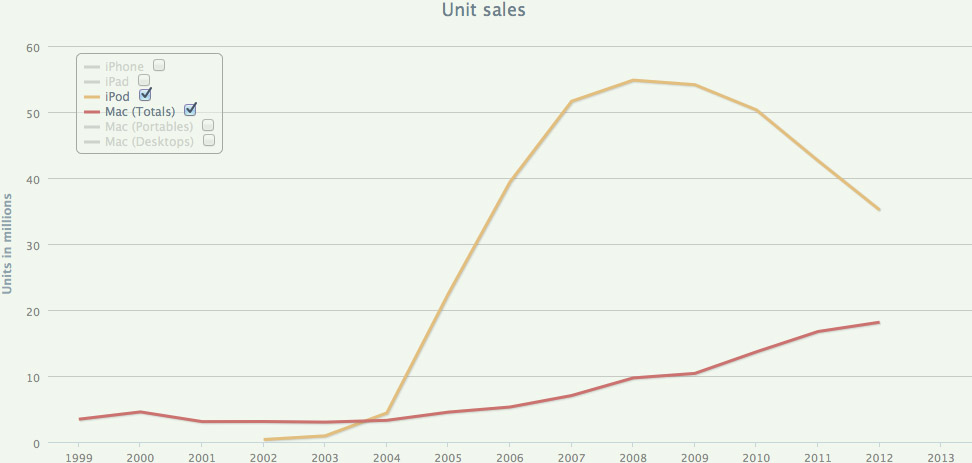

Here’s the same graph with iPods added:

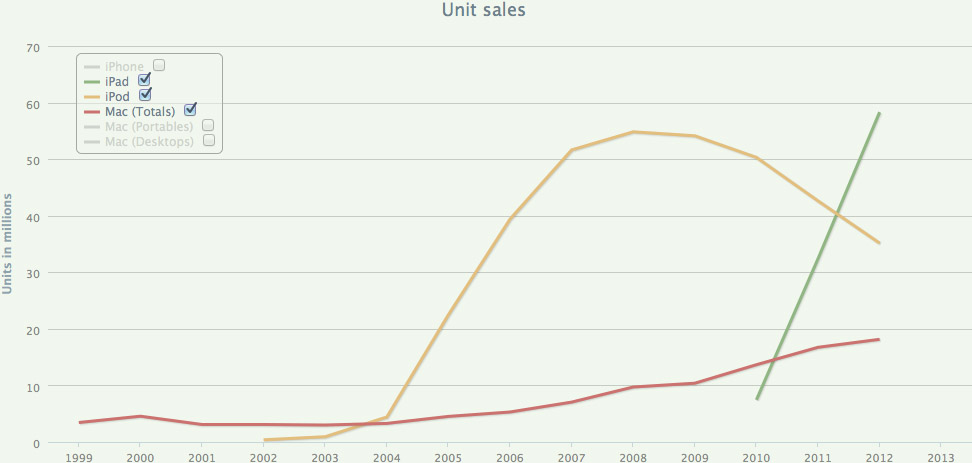

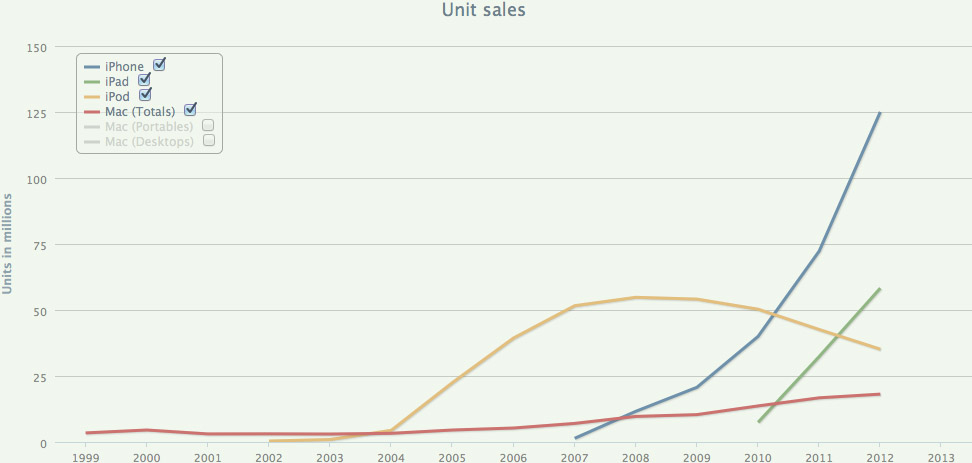

Here it is with iPads:

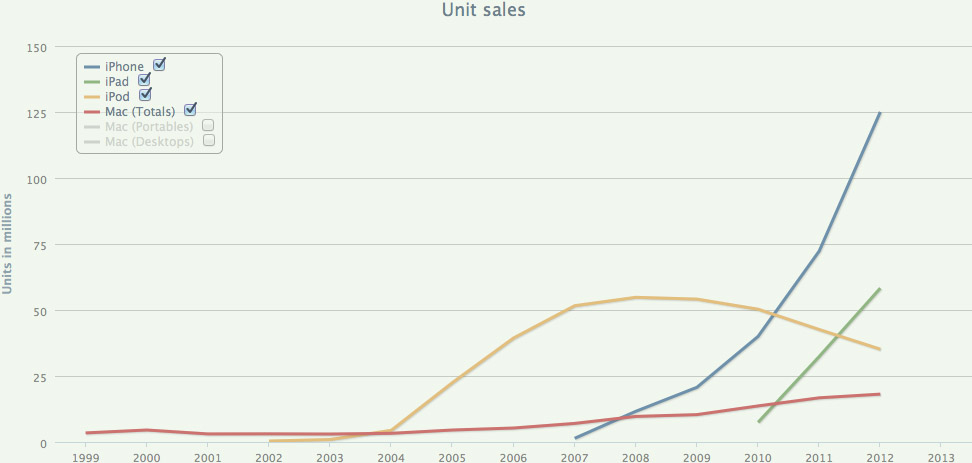

And finally, with iPhones too:

Notice that all of these graphs have something in common. Except for the iPod, they’re all currently going up. And except for the iPod’s sudden rocket-blast-off around 2004-2005, there’s almost no sudden change in direction. The trajectories are all very consistent, and experience only gradual change in direction over a period of several years.

This all strongly suggests, of course, that Apple is very unlikely to find itself in any kind of serious trouble for many years to come, at least. But you wouldn’t know it to read many pundits’ dire predictions of near-term Apple decline.

Graphic Failure

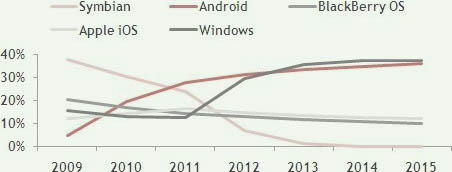

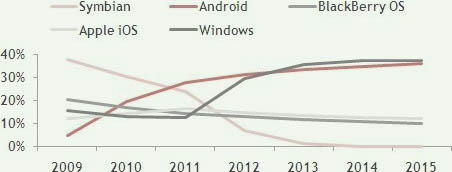

Most of these down-on-Apple commentators don’t grace us with a graph of their predictions, but every now and then they do. Here’s exactly such a graph from Pyramid Research:

Graphs look authoritative, don’t they? And this one seems to indicate that Windows and Android will be neck-and-neck winners in the mobile computing space (Windows arbitrarily slightly ahead of Android), iOS and Blackberry will be tied for a very distant third-and-fourth place, and Symbian will be dead and forgotten.

Now, let’s draw some lines over this graph and see what’s happening with it:

The green line represents the present, i.e. when the graph was created. Everything to the left of the green line is actual data (perhaps skewed with “shipments” tricks, but for the sake of the argument, we’ll assume it’s valid). Everything to the right of the green line is predictions (projections, forecasts, whatever).

The emphasized line represents Android. As you can see, up to the present it is increasing, but progressively more slowly. And after the green line, it continues to do exactly that, with no noticeable inflection point at the green line. So this can be considered a reasonable projection of the past into the future. Of course, there’s no guarantee that that’s exactly what will happen. And the farther you project the past into the future, the less likely it will be to happen that way. (And this graph projects pretty far into the future, you’ll notice.) But still — a reasonable projection.

Next, here’s what they did for BlackBerry:

Again, a reasonable projection. The line is going down, but progressively more slowly. The future line continues that same trend with no noticeable change.

Now — here’s Symbian:

That’s weird. Why the big inflection point right at the present? Don’t get me wrong; at the time this graph was made, I had no quibble with the general idea that Symbian was in severe decline, nor that it would be effectively dead several years later. Nor do I dispute that thesis today. But still — why the big change in direction right at the green line — the time when the graph was created? That’s very suspicious. I suggest that this big dip is necessary to make the graph add up to 100% over its whole range: What we’re about to see below (regarding iOS and Windows) is why Symbian has to take a suddenly steeper dive at the green line.

Now for iOS:

The past showed iOS climbing at a slightly increasing rate. Then suddenly, at the green line, it changes direction to downward. And does so at just the right speed so that it can be arbitrarily ahead of BlackBerry but otherwise as small as possible.

All of these predictions leave just enough room in the 100% total for Windows to do this:

It takes a huge and abrupt upturn at the green line, and winds up barely in first place, just the tiniest bit ahead of Android.

Now, I leave it to the reader to ponder: What are the chances that this graph was made by any predictive technique more sophisticated than, “Somehow, we have to predict market victory for Microsoft. How can we bend and twist these lines to make that outcome occur, while still keeping the graph total at 100%?”

Backhanded Compliment

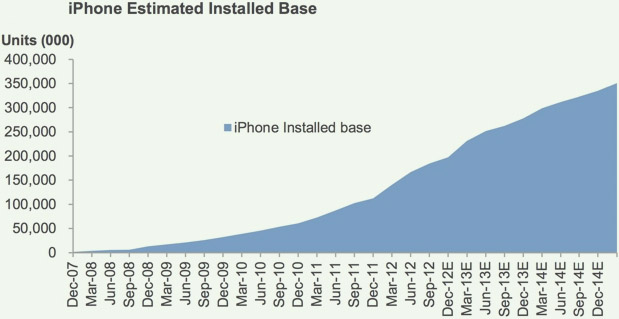

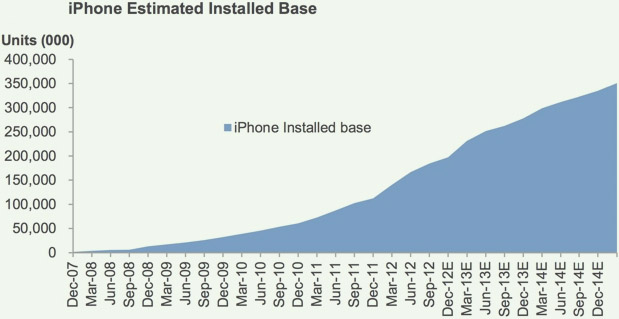

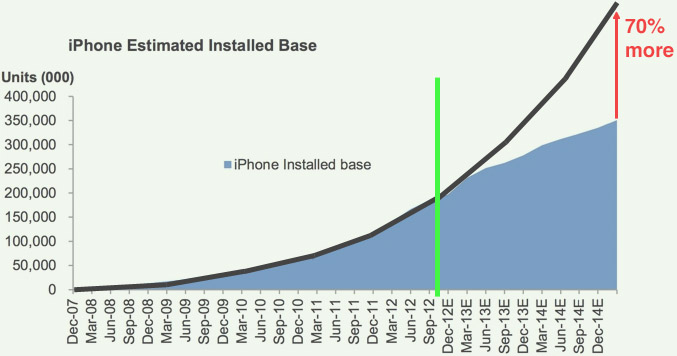

Even when market analysts seem to be saying something positive about Apple, it’s not always so. Consider this graph of “iPhone Estimated Installed Base” from Rob Cihra of Evercore Partners:

Hey, that looks positive, doesn’t it? Climbing at a nice, healthy rate. No abrupt downturns. What could be anti-Apple about that?

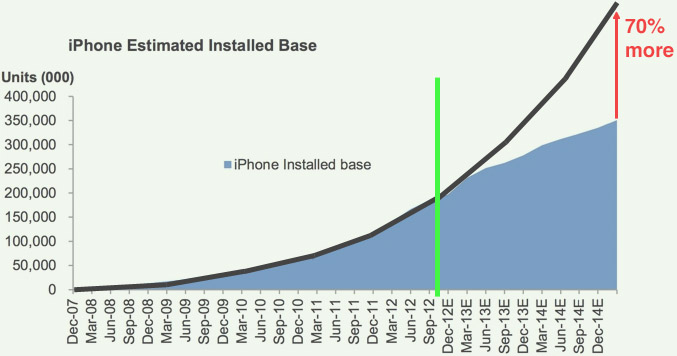

But notice that the graph’s title included the word “Estimated.” And notice all those “E”s starting in December of 2012 — they’re easy to overlook, and they’re the only indication that those quarters are “estimated,” not actual. So now take a look at the exact same graph with a big, fat, green present-line on it, plus a reasonable (my freehand) continuation of the past into the future:

Ugh. The reasonable projection turns out to be about 70% greater than Cihra’s “estimate.” His graph has no obvious change in direction that pops out as in Pyramid’s, but still: an arbitrary and massive reduction in Apple’s future potential, with no basis in past performance.

Future Uncertain

Now, again — and I can’t emphasize this enough — I have no way of knowing what Apple’s future holds. It might be much better than a reasonable projection of its past, or it might be much worse. It might even be worse than Pyramid and Evercore said it would be; who knows?

My point is simply that when you look at forecasts of how Apple and its competitors will be doing in the next several years, keep in mind that there’s a good chance that the forecast is being made by people who have little or no interest in how their predictions will look a few years from now. They simply want to be negative about Apple today, and they use their analyst position to do so.

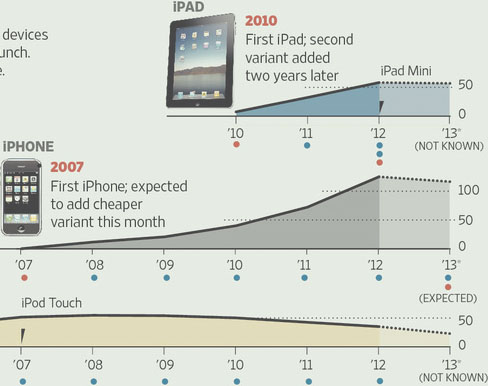

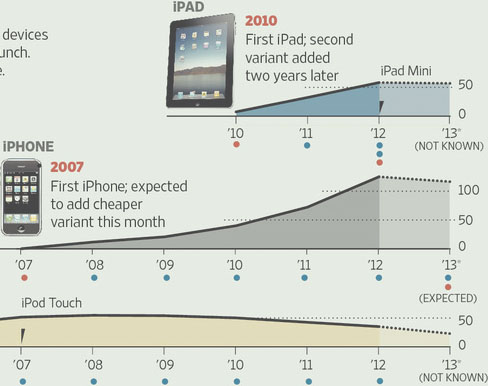

Update 2013.09.10 — The Wall Street Journal’s recent graphs showing the very-near-future of all three iOS devices:

To their credit, they’re going only one year (or less) out, and they make the not-actual-data portion very visibly different from the actual-data portion. And the iPod Touch curve is only the tiniest bit worse than a reasonable projection of its very smooth, many-year curve. But what’s up with the other two graphs? Can you say, “massive downward-bending cusp at the now-line, with no other noticeable cusp in the history of the product?” I knew you could.

prev next

Hear, hear

prev next

Best recent articles

Make Your Own FBI Backdoor, Right Now

Polygon Triangulation With Hole

The Legacy of Windows Phone

Palm Fan

Vivek Wadhwa, Scamster Bitcoin Doomsayer

Fanboy Features (regularly updated)

When Starting A Game of Chicken With Apple, Expect To Lose — hilarious history of people who thought they could bluff Apple into doing whatever they wanted.

A Memory of Gateway — news chronology of Apple’s ascendancy to the top of the technology mountain.

iPhone Party-Poopers Redux and Silly iPad Spoilsports — amusing litanies of industry pundits desperately hoping iPhone and iPad will go away and die.

Embittered Anti-Apple Belligerents — general anger at Apple’s gi-normous success.

RSS FEED

My books

Now available on Apple Books!

Links

Daring Fireball

The Loop

RoughlyDrafted

Macalope

Red Meat

Despair, Inc.

Real Solution #9 (Mambo Mania Mix) over stock nuke tests. (OK, somebody made them rip out the music — try this instead.)

Ernie & Bert In Casino

Great Explanation of Star Wars

Best commercials (IMO) from Super Bowl 41, 43, 45, 46, 47, 53 and 55

Kirk & Spock get Closer

American football explained.

TV: Severance; Succession; The Unlikely Murderer; Survivor; The Jinx; Breaking Bad; Inside Amy Schumer

God’s kitchen

Celebrity Death Beeper — news you can use.

Making things for the web.

RedQueenCoder.

My vote for best commercial ever. (But this one’s a close second, and I love this one too.)

Recent commercials I admire: KFC, Audi, Volvo

Best reggae song I’ve discovered in quite a while: Virgin Islands Nice

Aquarium by Saint-Saëns. What a superb performance, easily the equal of the Bernstein recording I grew up with. And so nice to see it performed up close in a high-quality video. But how awful when YouTube popovers spoil the final seconds, and an incredibly loud ad starts playing as soon as the music stops. Sickening. I guess this is the price we pay for having free, immediate access to such beautiful works of art.

d120 dice: You too (like me) can be the ultimate dice nerd.

WiFi problems? I didn’t know just how bad my WiFi was until I got eero.

Favorite local pad thai: Pho Asian Noodle on Lane Ave. Yes, that place; blame Taco Bell for the amenities. Use the lime, chopsticks, and sriracha. Yummm.

Um, could there something wrong with me if I like this? Or this?

Reggae recreation of Ozzy singing Iron Man. The cheery melancholy of the style, and the clarity of the lyrics, make the story sadder and realer to me.

This entire site as a zip file — last updated 2025.09.03

Previous articles

The West Coast Is Totally Doomed

Malicious Requirement, Non-Malicious Compliance

Well-Regulated Militia

Stroking Their Bruised Egos

EU vs Apple

Scioto Grove Tower NOPE

Fitness Startup Is Hard

Sweeney Translation

Collatz, Revisited

Downtown Isn’t Coming Back

Stig

Gaston

Nuclear War

Wolfspeare

Engström’s Motive

Google’s Decision

Warrening

The Two Envelopes Problem, Solved

The Practical Smartphone Buyer

Would Apple Actually Exit the EU Or UK?

See You Looked

Blackjack Strategy Card (Printable)

Swan Device 1956 — Probable Shape

Pu

RGB-To-Hue Conversion

Polygon Triangulation With Hole

One-Point Implosion: “Palm Fan”

Implosion: Were Those Two-Speed Lenses Really Necessary?

Apple Wants User/Developer Choice; Its Enemies Want Apple Ruin

Tim Sweeney Plays Dumb

The Jury of One

The Lesson of January 6

Amnesia Is Not A Good Plot

I Was Eating for 300 lbs, Not 220

Action Arcade Sounds and Reality

The Flea Market and the Retail Store

Squaring the Impossible

Yes, Crocodiles Are Dinosaurs — Duh

Broccoli and Apples Are Not the Antidote To Donuts and Potato Chips

Cydia and “Competition”

The Gift of Nukes

Prager University and the Anti-Socialists’ Big Blind Spot

In Defense of Apple’s 30% Markup, Part 2

In Defense of Apple’s 30% Markup

Make Your Own FBI Backdoor, Right Now

Storm

The Legacy of Windows Phone

Mindless Monsters

To the Bitter End

“Future Shock” Shock

Little Plutonium Boy

The iPhone Backdoor Already Exists

The Impulse To Be Lazy

HBO’s “Meth Storm” BS

Judos vs. Pin Place

Vizio M-Series 65" LCD (“LED”) TV — Best Settings (IMHO)

Tasting Vegemite (Bucket List)

The IHOP Coast

The Surprise Quiz Paradox, Solved

Apple, Amazon, Products, and Services — Not Even Close

Nader’s Open Blather

Health — All Or Nothing?

Vivek Wadhwa, Scamster Bitcoin Doomsayer

Backwards Eye Wiring — the Optical Focus Hypothesis

Apple’s Cash Is Not the Key

Nothing More Angry Than A Cornered Anti-Apple

Let ’Em Glow

The Ultimate, Simple, Fair Tax

Compassion and Vision

When Starting A Game of Chicken With Apple, Expect To Lose

The Caveat

Superb Owl

NavStar

Basic Reproduction Number

iBook Price-Fixing Lawsuit Redux — Apple Won

Delusion Made By Google

Religion Is A Wall

It’s Not A Criticism, It’s A Fact

Michigan Wolverines 2014 Football Season In Review

Sprinkler Shopping

Why There’s No MagSafe On the New MacBook

Sundar Pichai Says Devices Will Fade Away

The Question Every Apple Naysayer Must Answer

Apple’s Move To TSMC Is Fine For Apple, Bad For Samsung

Method of Implementing A Secure Backdoor In Mobile Devices

How I Clip My Cat’s Nails

Die Trying

Merger Hindsight

Human Life Decades

Fire and the Wheel — Not Good Examples of A Broken Patent System

Nobody Wants Public Transportation

Seasons By Temperature, Not Solstice

Ode To Coffee

Starting Over

FaceBook Messenger — Why I Don’t Use It

Happy Birthday, Anton Leeuwenhoek

Standard Deviation Defined

Not Hypocrisy

Simple Guide To Progress Bar Correctness

A Secure Backdoor Is Feasible

Don’t Blink

Predictive Value

Answering the Toughest Question About Disruption Theory

SSD TRIM Command In A Nutshell

The Enderle Grope

Aha! A New Way To Screw Apple

Champagne, By Any Other Maker

iOS Jailbreaking — A Perhaps-Biased Assessment

Embittered Anti-Apple Belligerents

Before 2001, After 2001

What A Difference Six Years Doesn’t Make

Stupefying New Year’s Stupidity

The Innovator’s Victory

The Cult of Free

Fitness — The Ultimate Transparency

Millions of Strange Devotees and Fanatics

Remember the iPod Killers?

Theory As Simulation

Four Analysts

What Was Christensen Thinking?

The Grass Is Always Greener — Viewing Angle

Is Using Your Own Patent Still Allowed?

The Upside-Down Tech Future

Motive of the Anti-Apple Pundit

Cheating Like A Human

Disremembering Microsoft

Security-Through-Obscurity Redux — The Best of Both Worlds

iPhone 2013 Score Card

Dominant and Recessive Traits, Demystified

Yes, You Do Have To Be the Best

The United States of Texas

Vertical Disintegration

He’s No Jobs — Fire Him

A Players

McEnroe, Not Borg, Had Class

Conflict Fades Away

Four-Color Theorem Analysis — Rules To Limit the Problem

The Unusual Monopolist

Reasonable Projection

Five Times What They Paid For It

Bypassable Security Certificates Are Useless

I’d Give My Right Arm To Go To Mars

Free Advice About Apple’s iOS App Store Guidelines

Inciting Violence

One Platform

Understanding IDC’s Tablet Market Share Graph

I Vote Socialist Because...

That Person

Product Naming — Google Is the Other Microsoft

Antecessor Hypotheticum

Apple Paves the Way For Apple

Why — A Poem

App Anger — the Supersized-Mastodon-In-the-Room That Marco Arment Doesn’t See

Apple’s Graphic Failure

Why Microsoft Copies Apple (and Google)

Coders Code, Bosses Boss

Droidfood For Thought

Investment Is Not A Sure Thing

Exercise is Two Thirds of Everything

Dan “Real Enderle” Lyons

Fairness

Ignoring the iPod touch

Manual Intervention Should Never Make A Computer Faster

Predictions ’13

Paperless

Zeroth — Why the Century Number Is One More Than the Year Number

Longer Than It Seems

Partners: Believe In Apple

Gun Control: Best Arguments

John C. Dvorak — Translation To English

Destructive Youth

Wiens’s Whine

Free Will — The Grand Equivocation

What Windows-vs.-Mac Actually Proved

A Tale of Two Logos

Microsoft’s Three Paths

Amazon Won’t Be A Big Winner In the DOJ’s Price-Fixing Suit

Infinite Sets, Infinite Authority

Strategy Analytics and Long Term Accountability

The Third Stage of Computing

Why 1 Isn’t Prime, 2 Is Prime, and 2 Is the Only Even Prime

Readability BS

Lie Detection and Psychos

Liking

Steps

Microsoft’s Dim Prospects

Humanity — Just Barely

Hanke-Henry Calendar Won’t Be Adopted

Collatz Conjecture Analysis (But No Proof; Sorry)

Rock-Solid iOS App Stability

Microsoft’s Uncreative Character

Microsoft’s Alternate Reality Bubble

Microsoft’s Three Ruts

Society’s Fascination With Mass Murder

PlaysForSure and Wikipedia — Revisionism At Its Finest

Procrastination

Patent Reform?

How Many Licks

Microsoft’s Incredible Run

Voting Socialist

Darwin Saves

The Size of Things In the Universe

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy That Wasn’t

Fun

Nobody Was In Love With Windows

Apples To Apples — How Anti-Apple Pundits Shoot Themselves In the Foot

No Holds Barred

Betting Against Humanity

Apple’s Premium Features Are Free

Why So Many Computer Guys Hate Apple

3D TV With No Glasses and No Parallax/Focus Issues

Waves With Particle-Like Properties

Gridlock Is Just Fine

Sex Is A Fantasy

Major Player

Why the iPad Wannabes Will Definitely Flop

Predators and Parasites

Prison Is For Lotto Losers

The False Dichotomy

Wait and See — Windows-vs-Mac Will Repeat Itself

Dishonesty For the Greater Good

Barr Part 2

Enough Information

Zune Is For Apple Haters

Good Open, Bad Open

Beach Bodies — Who’s Really Shallow?

Upgrade? Maybe Not

Eliminating the Impossible

Selfish Desires

Farewell, Pirate Cachet

The Two Risk-Takers

Number of Companies — the Idiocy That Never Dies

Holding On To the Solution

Apple Religion

Long-Term Planning

What You Have To Give Up

The End of Elitism

Good and Evil

Life

How Religion Distorts Science

Laziness and Creativity

Sideloading and the Supersized-Mastodon-In-the-Room That Snell Doesn’t See

Long-Term Self-Delusion

App Store Success Won’t Translate To Books, Movies, and Shows

Silly iPad Spoilsports

I Disagree

Five Rational Counterarguments

Majority Report

Simply Unjust

Zooman Science

Reaganomics — Like A Diet — Works

Free R&D?

Apple’s On the Right Track

Mountains of Evidence

What We Do

Hope Conquers All

Humans Are Special — Just Not That Special

Life = Survival of the Fittest

Excuse Me, We’re Going To Build On Your Property

No Trademark iWorries

Knowing

Twisted Excuses

The Fall of Google

Real Painters

The Meaning of Kicking Ass

How To Really Stop Casual Movie Disc Ripping

The Solitary Path of the High-Talent Programmer

Fixing, Not Preaching

Why Blackmail Is Still Illegal

Designers Cannot Do Anything Imaginable

Wise Dr. Drew

Rats In A Too-Small Cage

Coming To Reason

Everything Isn’t Moving To the Web

Pragmatics, Not Rights

Grey Zone

Methodologically Dogmatic

The Purpose of Language

The Punishment Defines the Crime

Two Many Cooks

Pragmatism

One Last Splurge

Making Money

What Heaven and Hell Are Really About

America — The Last Suburb

Hoarding

What the Cloud Isn’t For

Diminishing Returns

What You’re Seeing

What My Life Needs To Be

Taking An Early Retirement

Office Buildings

A, B, C, D, Pointless Relativity

Stephen Meyer and Michael Medved — Where Is ID Going?

If You Didn’t Vote — Complain Away

iPhone Party-Poopers Redux

What Free Will Is Really About

Spectacularly Well

Pointless Wrappers

PTED — The P Is Silent

Out of Sync

Stupid Stickers

Security Through Normalcy

The Case For Corporate Bonuses

Movie Copyrights Are Forever

Permitted By Whom?

Quantum Cognition and Other Hogwash

The Problem With Message Theory

Bell’s Boring Inequality and the Insanity of the Gaps

Paying the Rent At the 6 Park Avenue Apartments

Primary + Reviewer — An Alternative IT Plan For Corporations

Yes Yes Yes

Feelings

Hey Hey Whine Whine

Microsoft About Microsoft Visual Microsoft Studio Microsoft

Hidden Purple Tiger

Forest Fair Mall and the Second Lamborghini

Intelligent Design — The Straight Dope

Maxwell’s Demon — Three Real-World Examples

Zealots

Entitlement BS

Agenderle

Mutations

Einstein’s Error — The Confusion of Laws With Their Effects

The Museum Is the Art

Polly Sooth the Air Rage

The Truth

The Darkness

Morality = STDs?

Fulfilling the Moral Duty To Disdain

MustWinForSure

Choice

Real Design

The Two Rules of Great Programming

Cynicism

The End of the Nerds

Poverty — Humanity’s Damage Control

Berners-Lee’s Rating System = Google

The Secret Anti-MP3 Trick In “Independent Women” and “You Sang To Me”

ID and the Large Hadron Collider Scare

Not A Bluff

The Fall of Microsoft

Life Sucks When You’re Not Winning

Aware

The Old-Fashioned Way

The Old People Who Pop Into Existence

Theodicy — A Big Stack of Papers

The Designed, Cause-and-Effect Brain

Mosaics

IC Counterarguments

The Capitalist’s Imaginary Line

Education Isn’t Everything

I Don’t Know

Funny iPhone Party-Poopers

Avoiding Conflict At All Costs

Behavior and Free Will, Unconfused

“Reduced To” Absurdum

Suzie and Bubba Redneck — the Carriers of Intelligence

Everything You Need To Know About Haldane’s Dilemma

Darwin + Hitler = Baloney

Meta-ware

Designed For Combat

Speed Racer R Us

Bold — Uh-huh

Conscious of Consciousness

Future Perfect

Where Real and Yahoo Went Wrong

The Purpose of Surface

Eradicating Religion Won’t Eradicate War

Documentation Overkill

A Tale of Two Movies

The Changing Face of Sam Adams

Dinesh D’Souza On ID

Why Quintic (and Higher) Polynomials Have No Algebraic Solution

Translation of Paul Graham’s Footnote To Plain English

What Happened To Moore’s Law?

Goldston On ID

The End of Martial Law

The Two Faces of Evolution

A Fine Recommendation

Free Will and Population Statistics

Dennett/D’Souza Debate — D’Souza

Dennett/D’Souza Debate — Dennett

The Non-Euclidean Geometry That Wasn’t There

Defective Attitude Towards Suburbia

The Twin Deficit Phantoms

Sleep Sync and Vertical Hold

More FUD In Your Eye

The Myth of Rubbernecking

Keeping Intelligent Design Honest

Failure of the Amiga — Not Just Mismanagement

Maxwell’s Silver Hammer = Be My Honey Do?

End Unsecured Debt

The Digits of Pi Cannot Be Sequentially Generated By A Computer Program

Faster Is Better

Goals Can’t Be Avoided

Propped-Up Products

Ignoring ID Won’t Work

The Crabs and the Bucket

Communism As A Side Effect of the Transition To Capitalism

Google and Wikipedia, Revisited

National Geographic’s Obesity BS

Cavemen

Theodicy Is For Losers

Seattle Redux

Quitting

Living Well

A Memory of Gateway

Is Apple’s Font Rendering Really Non-Pixel-Aware?

Humans Are Complexity, Not Choice

A Subtle Shift

Moralism — The Emperor’s New Success

Code Is Our Friend

The Edge of Religion

The Dark Side of Pixel-Aware Font Rendering

The Futility of DVD Encryption

ID Isn’t About Size or Speed

Blood-Curdling Screams

ID Venn Diagram

Rich and Good-Looking? Why Libertarianism Goes Nowhere

FUV — Fear, Uncertainty, and Vista

Malware Isn’t About Total Control

Howard = Second Coming?

Doomsday? Or Just Another Sunday

The Real Function of Wikipedia In A Google World

Objective-C Philosophy

Clarity From Cisco

2007 Macworld Keynote Prediction

FUZ — Fear, Uncertainty, and Zune

No Fear — The Most Important Thing About Intelligent Design

How About A Rational Theodicy

Napster and the Subscription Model

Intelligent Design — Introduction

The One Feature I Want To See In Apple’s Safari.

design by

design by